War Above and Fuel Below: Ukraine’s Drone Strategy Meets the Caspian Energy Pivot

Recent Articles

Author: Joshua Bernard-Pearl

02/26/2025

Image Source: Wikimedia - Ukraine's drone strikes against Russian oil infrastructure have driven up the price of Russian fuel exports and highlighted their unreliable nature. This has made alternative hydrocarbon sources from Central Asia and the Caucasus more attractive and competitive.

Ukraine launched 81 drone attacks on Russian oil refineries and storage depots as of December 2024, in what is a campaign planned to cripple Russia’s hydrocarbon infrastructure. While not a coordinated effort with the Caucasus and Central Asia, Ukraine’s strategy is fueling a Caspian energy realignment. At least 64 of Ukraine’s strikes resulted in fires or produced lasting damage to facilities. Ukrainian operations have been credited with dropping the volume of Russian oil refined to its lowest level in 12 years and a nearly 10% reduction in Russian seaborne oil exports in 2024. Although some facilities were eventually repaired, this took time, money, and specialized pieces of equipment often produced by Western countries hostile to Russia, only to be struck again. Ukrainian efforts have been relentless at draining Russian resources, hampering the security of its fuel supply, and inflicting a significant psychological blow to the Russian war machine.

Kyiv's decision on January 1 to shut off flows of Russian natural gas to Europe through the Brotherhood gas pipeline further eliminated Russian hydrocarbon revenues of approximately $6.2 billion annually. These Ukrainian efforts, combined with ongoing sanctions, have proven remarkably effective in cutting Russia off from European hydrocarbon revenue and at the same time have highlighted a dire need for Europe to diversify away from Russian fuel imports. In the absence of Russian oil and gas, Europe is left with a critical supply gap for its energy infrastructure.

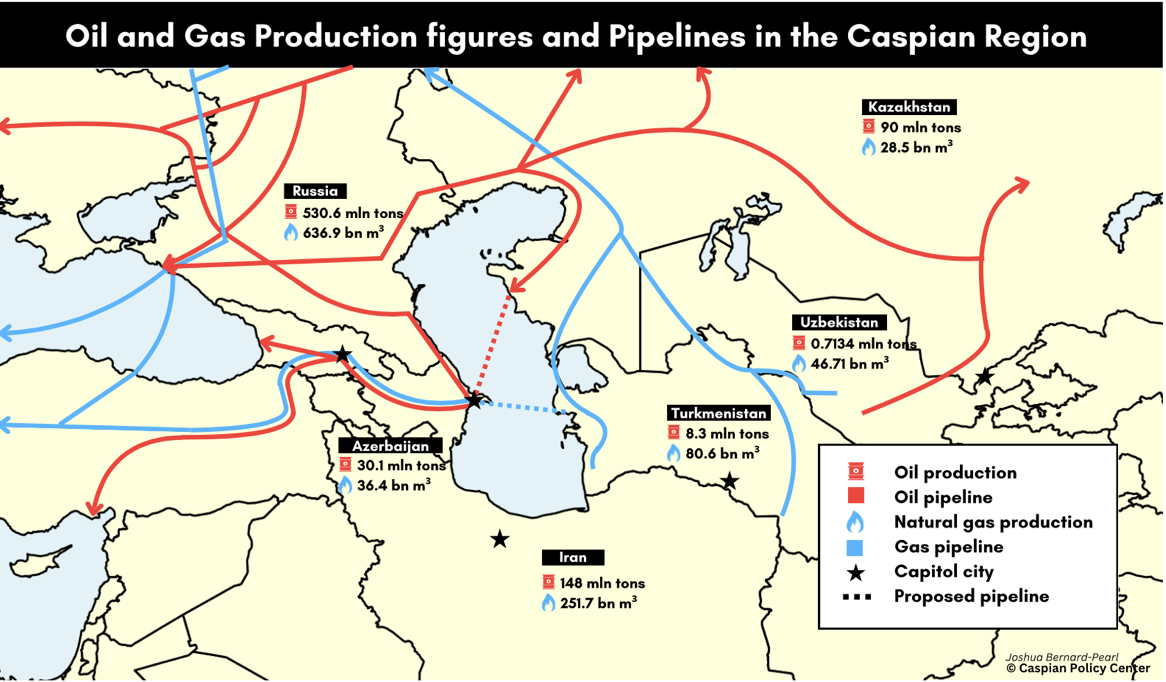

The Caspian region produces an abundance of oil and natural gas and already has a robust network of pipelines that could be utilized and further connected to European distribution channels.

The Caspian region produces an abundance of oil and natural gas and already has a robust network of pipelines that could be utilized and further connected to European distribution channels.

With its abundant reserves of oil and natural gas, and governments eager to expand commercial relationships, Central Asia and the Caucasus are emerging as a potential solution to fill this fuel gap. For Europe, trans-Caspian fuel can enable continued energy security amidst Russian embargos, while the broader Caspian region of Central Asian and the South Caucasus countries reaps new revenue and economic diversification away from neighbors Russia and China.

A robust network of oil and gas pipelines already exists within the region, however, many of these pipelines connect to the Russian system and have relied on Moscow for transport. This leaves them open to Russian interference and at risk of disruption from Ukrainian attacks on Russian infrastructure. Just this past week, a Ukrainian drone strike on a pumping station in southern Russia reportedly cut Kazakh oil exports by close to a third. Though abundant in hydrocarbon resources itself, the Caspian Sea stands as a dividing wall between resource-rich Central Asia and the South-Caucasus gateway to Europe because there exist no oil or gas pipelines connecting its eastern and western shores.

Southern Gas Corridor (SGC)

Wikimedia - The Southern Gas Corridor (SGC) consists of various pipelines connecting Caspian natural gas to Europe through Georgia, Turkey, Greece, and Italy. The SGC could replace Russia-centric transport networks that previously supplied gas to Europe.

Wikimedia - The Southern Gas Corridor (SGC) consists of various pipelines connecting Caspian natural gas to Europe through Georgia, Turkey, Greece, and Italy. The SGC could replace Russia-centric transport networks that previously supplied gas to Europe.

Azerbaijan is already a prominent player in the European energy market, exporting natural gas to 10 European countries in 2024. Since signing a Strategic Partnership Energy memorandum with the European Union in July 2022, Azerbaijan has sought to expand these commercial relationships. Turkey and Italy are the largest recipients of Azerbaijani gas, accounting for 38.2% and 38% of exports respectively, from January to November of 2024. Bulgaria was next, accounting for 12.6%, and has recently increased its imports to two billion cubic meters of gas imported in 2024.

Currently, Azerbaijan's main method of exporting natural gas is through the "Southern Gas Corridor" pipeline system, including the South Caucasus Pipeline (SCP), Trans-Anatolian Pipeline (TANAP), and the Trans Adriatic Pipeline (TAP) transporting gas from Azerbaijan through Georgia, Turkey, Greece, Albania, and Italy. Currently, the SCP has an annual capacity of 24.04 billion cubic meters (bcm) but that could be expanded to 31 bcm. On January 25, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky also announced that Ukraine was ready to transport Azerbaijani gas to Europe along a network of pipelines previously used to transport Russian gas; however, this would still require relying on pipeline infrastructure within Russia connecting Azerbaijan to Ukraine which could be subject to potential Russian interference.

Kazakhstan is another major producer of both natural gas and oil, with 70% of Kazakhstan’s oil exports going to the European Union while gas exports largely go to Russia and China. Historically a mixed bag for foreign investors, the country has a history of filing lawsuits with large claims against investors in what some have alleged is a strategy to increase the country’s shares in large oil and natural gas projects. This includes over $150 billion in claims against Exxon, Shell PLC, TotalEnergies SE, and Eni S.p.A involved with developing the Kashagan field located in the northern segment of the Caspian Sea. Despite these legal battles, however, Kazakh oil fields have continued to be profitable for international investors, spurring increased investments. On January 24, Chevron announced it had started production at a new $48 billion expansion of its facilities in the Tengiz oil field, estimated to bring the field's output to one percent of global crude supply.

Kazakhstan’s past oil export routes have largely flowed through Russia to the EU, through the Caspian Pipeline Consortium’s (CPC) pipeline. Following a Ukrainian drone strike on a CPC pumping station on February 18, Kazakh oil exports through the CPC have dropped by 30-40 percent. Repairs could take months according to Russian Deputy Prime Minister Alexander Novak. On January 27, however, Kazakhstan made its inaugural shipment of oil from its Kashagan field to Baku across the Caspian Sea via tanker, in order to distribute oil through the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan (BTC) Pipeline system through Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Turkey.

This effort was part of an initiative to diversify away from dependence on the CPC and Russian hydrocarbon infrastructure by strengthening the trans-Caspian middle corridor transport network. In April 2024, Kazakhstan’s Ministry of Energy also announced it was considering revisiting plans for a trans-Caspian oil pipeline along this same route from Aktau, Kazakhstan, to Baku, Azerbaijan, in order to increase the capacity and efficiency of this export route.

Kashagan Oil Field

Source: kmg.kz - Kazakhstan’s Kashagan oil field, located in the Caspian Sea, produces oil that is shipped through the SGC to the Caucasus and Europe.

Source: kmg.kz - Kazakhstan’s Kashagan oil field, located in the Caspian Sea, produces oil that is shipped through the SGC to the Caucasus and Europe.

Turkmenistan, Kazakhstan, and Uzbekistan are the largest producers of natural gas in Central Asia, while China is the largest importer of natural gas from the region. This is largely due to high demand from Beijing and a reliance on fixed pipeline infrastructure connecting Turkmenistan, Kazakhstan, and Uzbekistan with the market in China. However, given the recent increase in European demand for non-Russian natural gas, the three Central Asian countries could diversify their exports westward with the proper pipeline infrastructure investments. A trans-Caspian east-to-west gas pipeline was first raised by the United States in 1996; later a more limited project was proposed to connect offshore gas platforms in Turkmenistan with existing pipeline infrastructure extending into Azerbaijani waters.

Given this existing infrastructure, construction of a trans-Caspian pipeline could be accomplished in a relatively short period of time, but the project has long been stalled due to several obstacles, including a lack of funding and disagreements over demarcating the maritime boundaries between Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan. “The delimitation issues between Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan are real, they could be resolved easily, but I don’t see political will on either side of the Caspian Sea to follow through with the Trans-Caspian Gas Pipeline,” said former U.S. Ambassador to Turkmenistan Matthew Klimow, when speaking at the Caspian Policy Center.

“There is also the issue of demand,” he noted. “For a long time the Europeans were adamant that they don’t want fossil fuels at all, 'We are not going to buy any natural gas from Turkmenistan…’.” However, the retired ambassador added, “This attitude has changed, but there is still a weak demand signal from Europe and the EU for natural gas.” If European leaders are serious about finding new non-Russian sources of natural gas, Klimow believes stronger messaging in favor of Turkmen gas could go a long way in building the political will necessary to revitalize the trans-Caspian pipeline project.

Ukraine's efforts to cripple the Russian hydrocarbon industry have opened a golden opportunity for a new energy relationship between the Caspian region and Europe. The production capacity to meet European demands exists from Central Asia and the Caucasus countries, and much of the required infrastructure already exists. With the right political will, Europe and the Caspian region could break Russian dominance over the Eurasian energy market, ensuring greater energy independence for Europe and new economic opportunity for the Caspian region countries.