Visualizing Caspian Energy

Recent Articles

Author: Ali Dayar

03/06/2025

The left map highlights the major oil fields across Caspian littoral states, each possessing significant reserves. The right map illustrates the extensive network of pipeline routes in the region.

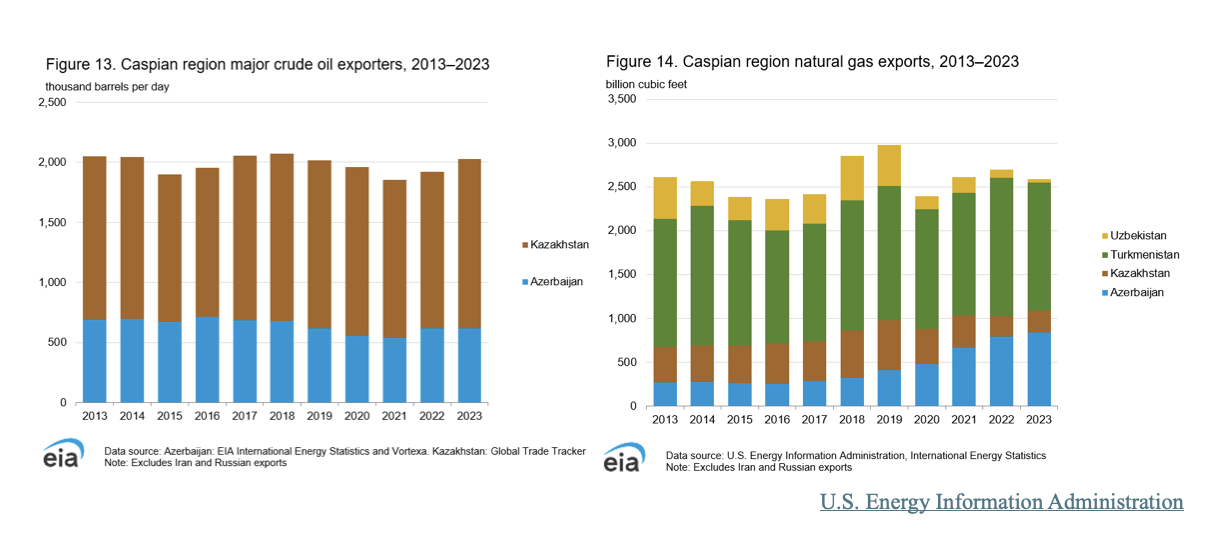

Caspian energy has gained unprecedented relevance in global markets. The disruption of traditional energy supply routes between Russia and Europe due to the war in Ukraine, as well as Russia’s pivot to the east, have intensified the role of Caspian states in diversifying the natural gas trade. Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan, Kazakhstan, and Uzbekistan have notably increased their supply of energy to the globe. While total exports of oil and gas in the region remained stable, major pipeline projects proliferated over the last ten years. The data and visuals released by the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) contextualizes these points, including the region’s legal challenges.

On February 6, EIA updated its analysis of energy in the Caspian Sea region. It offers insights into regional coal production, power generation, energy export routes, and a detailed overview of refinery operations in the area. EIA primarily focuses on Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. The analysis came 12 years after one dating from 2013. However, the next analysis is scheduled for February 2027, a remarkable increase in the frequency of Caspian energy analyses, reflecting the growing significance of Caspian energy for world markets.

The overview of the EIA analysis involves up-to-date energy production and export data of the regional countries. Azerbaijan holds seven billion barrels of oil and 60 trillion cubic feet (Tcf) of natural gas, with nearly all production occurring offshore. Kazakhstan produces 30 billion barrels of oil and 85 Tcf of natural gas. In 2024, it extracted 1.5 million barrels (b/d) of crude oil every day, 400,000 b/d of petroleum liquids, and one Tcf of natural gas, mostly for domestic use. Turkmenistan ranks fifth globally in proven natural gas reserves, with 400 Tcf. Uzbekistan extracts 594 million barrels of oil with a declining rate, reaching 63,000 b/d in 2024, about a third of its peak output 25 years earlier.

As major energy producers in the region, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and Turkmenistan have various markets that receive most of their fossil fuel exports. EU constitutes the majority for both the gas and oil for Azerbaijan through the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan (BTC) pipeline for oil and the Southern Gas Corridor (SGC) for gas. Astana exports most of its oil to the EU as well, through the Caspian Pipeline Consortium (CPC), despite having China as the primary purchaser of gas via the Central Asia-China pipeline. Ashgabat sells most of its gas through the same pipeline to China with negligible oil exports to China compared to gas. However, the legal status of the Caspian Sea remains convoluted.

Russia and Iran have traditionally argued that the Caspian should be treated as a lake, to which all five littoral states would have to agree to develop cross-border facilities such as pipelines. Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, and Turkmenistan, on the other hand, have advocated a median line demarcation by treating it as a sea, similar to an Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) regime, under which they would be able to develop projects unilaterally within their own zones. The 2018 Convention of the Legal Status of the Caspian Sea presented a middle ground that declared it an “intercontinental body of water” under national sovereignty over coastal waters and fishing but reserving the seabed for bilateral and trilateral relations. This structure gives the littoral states the power to veto or direct specific transboundary projects. Although Russia formally relinquished its veto on the Trans-Caspian Gas Pipeline, Moscow still claims an objection to the pipeline on environmental grounds. The convention grants the littoral countries full jurisdiction on pipelines within their zones, prohibiting Russia from explicitly stopping the project but potentially allowing Moscow to interfere indirectly via environmental conventions, despite the existence of thousands of miles of gas pipelines already in the Caspian.

Moreover, political and security uncertainty in Afghanistan are still obstacles to the construction of the Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India pipeline that Turkmenistan has long proposed and that it occasionally insists is already partly under construction. Both of these issues leverage Iran’s geopolitical position because Tehran allows Ashgabat to trade gas via swap arrangements using Iranian infrastructure, as per the Iraqi-Turkmen agreement signed last year and the recent agreement between Türkiye and Turkmenistan. Despite new connectivity opportunities, EIA data show Caspian oil and gas exports have remained stable over the past decade.

U.S. Energy Information Administration

U.S. Energy Information Administration

The figures show that the volume of oil and gas exports between 2013-2023 did not experience significant changes. EIA highlights that in 2022, offshore petroleum production in the Caspian Sea contributed over one million b/d, accounting for one percent of global petroleum supply, and over four Tcf of natural gas, making up nearly three percent of global supply. These figures underscore the Caspian region's steady role in global energy markets, despite legal challenges. While export volumes remained stable, the increasing interest in alternative routes and supply diversification highlights the region’s importance. Moving forward, enhanced connectivity, new pipeline projects, and evolving geopolitical dynamics will likely shape the Caspian’s contribution to global energy security.