Uzbekistan: A New Linchpin in China’s Central Asia Policy?

Recent Articles

Author: Dante Schulz

04/19/2021

On March 31, Uzbekistan’s Minister of Investment and Foreign Trade Sardor Umurzakov and China’s Minister of Commerce Wang Wentao met virtually to discuss China-Uzbekistan economic relations and key areas for bolstering cooperation. Specific topics included expanding investment ties, adopting innovative Chinese technology in Uzbek infrastructure projects, and enhancing trade.

The advancement of the China-Uzbekistan working relationship comes as there is a rise in resentment of Beijing in Central Asia. Hundreds gathered in Kazakhstan to protest China’s increasing economic power in Central Asia’s largest country last week and a Kyrgyz-led protest prompted Beijing to withdraw from a $280 million logistics center in February 2020. However, Uzbekistan’s relationship with its East Asian partner has steadily improved since President Shavkat Mirziyoyev sponsored market liberalization reforms. Uzbekistan could serve as a new linchpin for China’s economic inroads in Central Asia.

In 2013, Chinese President Xi Jinping launched the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which would expand infrastructure, economic, and other ties across Eurasia, thus boosting China’s influence while reviving ancient Silk Road trade routes. Kazakhstan is often described as the “buckle” of the BRI, but Uzbekistan could emerge as a viable contender for that role. Since 2017, Uzbekistan has enacted a range of market liberalization reforms to boost its economy and make it more attractive for western foreign direct investment and other business. However, it seems China may also intend to take advantage of the country’s more open business environment. Uzbekistan is emerging as a hub for Chinese manufacturing, putting the country in pole position to receive an influx of Chinese investment.

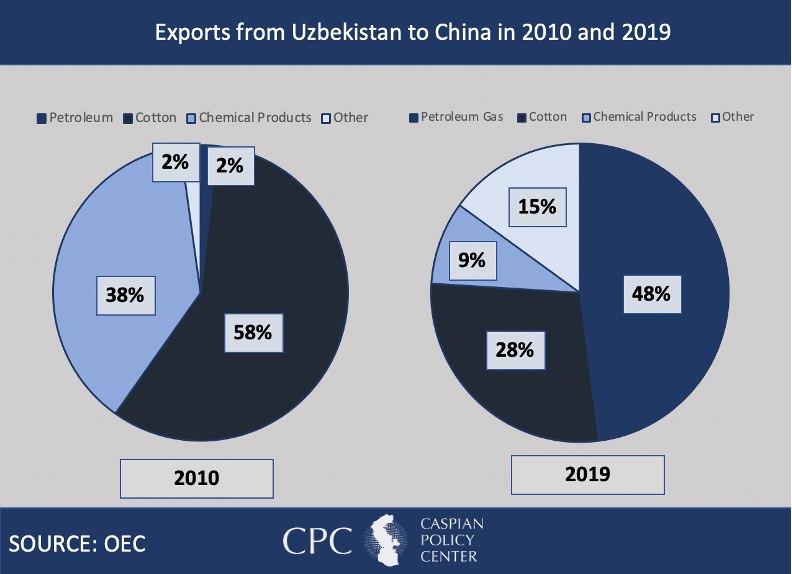

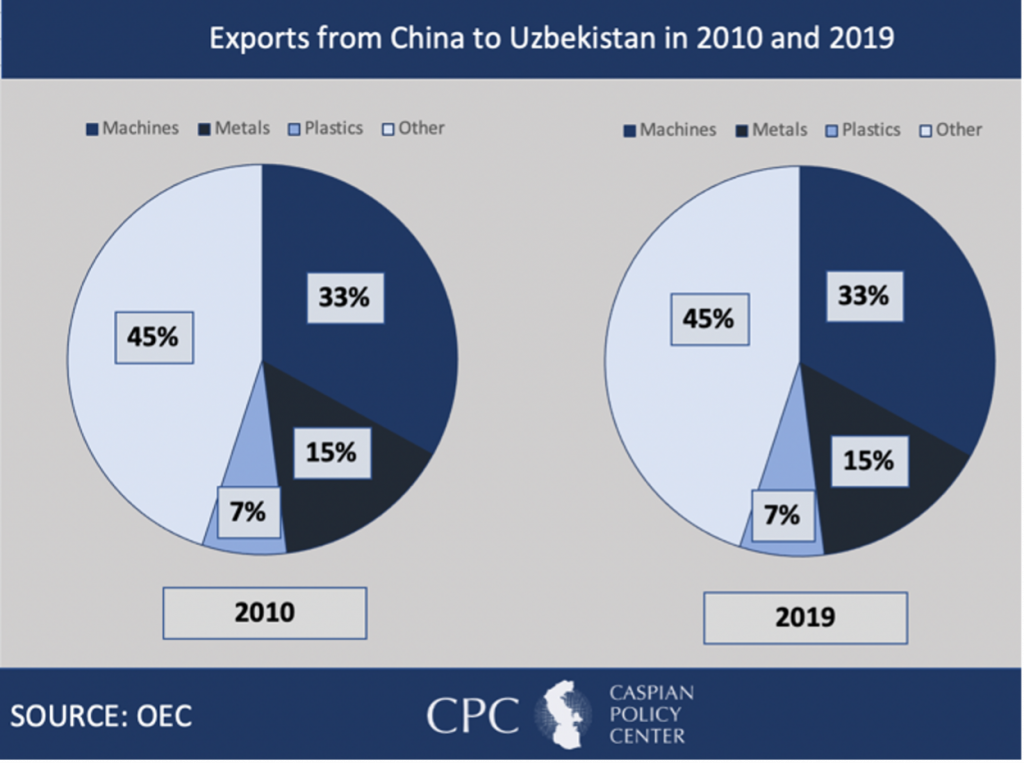

Uzbekistan’s working relationship with China is not riddled with as many security and economic hurdles as other Central Asian republics, which also helps it benefit from enhanced relations with China. Trade between the two countries skyrocketed over the past decade; in 2010, bilateral trade between Uzbekistan and China amounted to $2.44 billion, but this figure jumped to $6.92 billion by 2019. In addition, the products exchanged between the two countries have changed. In 2010, raw cotton accounted for over 50 percent of exports from Uzbekistan to China, but this dropped to under 10 percent nine years later, illustrating China’s growing interest in Uzbekistan’s hydrocarbon sector. In 2019, petroleum gas made up for about 47 percent of Uzbek exports to China. Furthermore, Chinese exports to Uzbekistan now include machinery and technology capable of completing large infrastructure projects.

China and Uzbekistan have also made considerable headway in establishing credit lines and supporting joint investment funds. In March 2013, Uzbekistan opened the Dhizak Free Industrial Zone in its Syrdarya region to facilitate Chinese-Uzbek investment exchanges. Furthermore, 1,652 enterprises operating in Uzbekistan — 16 percent of all enterprises in the country — benefit from Chinese investments. Moreover, in December 2019, Uzbekistan acquired a $2.3 billion investment package from China, South Korea, Japan, and Russia to finance a gas-to-liquids production facility. Incentives to attract FDI to Uzbekistan and Uzbek businesses craving foreign capital have allowed China to assume a prominent role in its economic development strategy.

However, not all of Uzbekistan is embracing China with open arms. In 2020 Central Asia Barometer discovered that only 26 percent of Uzbeks were confident Chinese investment would spur employment, an eight percentage points drop lower than the year before. Similarly, the percentage of Uzbeks concerned that BRI projects could result in a large growth in the amount of debt owed China increased from seven percent in 2019 to 25 percent a year later. While Uzbeks appear to be more welcoming of Chinese ventures than others in the region, the number of Uzbeks expressing concern about China’s economic presence is growing.

Uzbekistan historically has also had very strong ties to Russia and continues to maintain a robust dialogue with Moscow. In December 2020, Uzbekistan was granted observer status in the Russian-led economic bloc, the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU), resulting in a series of changes to align more closely with the regulations of the bloc. Russia also serves as the top destination for Uzbekistan citizens working abroad as seasonal migrants. In 2019, the vast majority of Uzbeks with international work visas went to Russia, highlighting the country’s sustained pull. It is more likely that Uzbekistan’s expanded cooperation with China is yet another manifestation of Central Asia’s trademark multi-vector foreign policy than it is a decisive pivot.

Uzbekistan and China enjoy a productive working relationship. Mirziyoyev’s reforms have fostered an environment conducive to Chinese investment and BRI infrastructure projects. In addition, the lack of border disputes removes anxieties over a possible Chinese military presence. However, Tashkent must also ensure it does not inflame domestic concerns over a growing Chinese profile; events in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan show where public opinion could trend. For now, Uzbekistan will likely continue to develop as a hub for Chinese investment and other economic engagement.