Caspian Policy Center Perspective: Food Security in Central Asia during an Economic Downturn

Recent Articles

Author: Caspian Policy Center

04/16/2020

The current economic downturn's impact on Central Asian food security will likely be less profound than in more urbanized societies more heavily dependent on commercial farming and international trade. Unlike those in Western, globalized economies, the populations of the five Central Asian nations remain heavily rural, and most rural dwellers practice self-sufficiency in basic staples with the exception of wheat and wheat flour for cooking cracked wheat dishes and baking bread. In addition, urban dwellers in these countries residing in single-family dwellings often keep livestock and maintain gardens. However, vulnerable populations exist, and their food security is at risk.

According to FAO data, Kazakhstan is the most urbanized of the five, at slightly under 43 percent rural, followed by Turkmenistan (48), Uzbekistan (49.5), Kyrgyzstan (64), and Tajikistan (73). For those countries offering statistical data, rural residence and poverty are highly correlated, and this partially explains the heavy reliance on gardening and small-scale animal husbandry to ensure food supplies at the rural family level. In the absence of cash, soil plus water plus seeds plus some sweat can keep the family fed.

Another explanation is imposition of the Russo-Soviet structure of agricultural production during collectivization of agriculture in the 1930s. Large farms were devoted to production of industrial cash crops like cotton and wheat, while private plots, euphemistically called "personal subsidiary agriculture", were expected to keep the countryside nourished. Forty years ago, half of all food produced in the Soviet Union came from 4% of the arable land, which was the area under private plots, and that included the majority of potatoes, fruits, vegetables, and eggs. Half of that output – a quarter of food supplies overall – was produced inside city limits, in urban and peri-urban gardens.

That model has not changed dramatically over the intervening years, as residents of Central Asian cities, accustomed to the sounds of crowing roosters and lowing cows, can attest. Thus, ironically, in terms of food security the least affected Central Asians during a recession are the poorest as long as they have access to land and water. That said, undernutrition is a chronic problem in rural Central Asia. In Tajikistan, for example, the World Bank found that over 20 percent of children under age 5 are stunted, largely due to undernutrition and malnutrition, and the majority of them are in rural areas. Thus, though food insecurity may be less drastic in rural areas of Central Asia, it is nonetheless a serious problem.

The picture is different for urban dwellers in apartment buildings, who have no access to land for producing food, and who rely almost exclusively on retail outlets for nutrition. As Central Asian leaders have sought to modernize, they have pushed residents out of traditional housing with courtyards and gardens into "modern" high-rises lacking dirt to play in. High and rising unemployment is a serious threat to food security in this segment of the urban population. Tajikistan's and Kyrgyzstan's heavy dependence on foreign remittances for a large proportion of GDP is an economic Achilles heel in light of Russia's restrictions on migrant labor due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

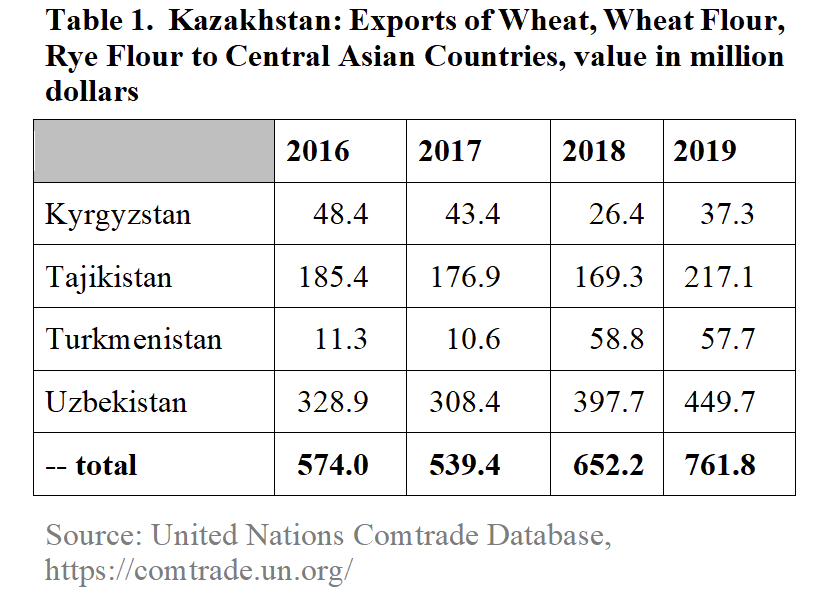

In addition, poor wheat crops in Turkmenistan have created a dependence on imports of flour from Kazakhstan, payable only with hard currency, and Turkmenistan's hard currency woes have thus resulted in flour and bread shortages even in provincial capitals. Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, as mountainous countries unsuited for large-scale grain production, as well as arid Uzbekistan, already depend on Kazakhstan for wheat and flour. Since even rural dwellers in Central Asia buy wheat and wheat flour and do not grow it themselves, flour and bread availability presents itself as the single most important food security issue facing the region. That said, the sums of money involved are relatively small. In 2019 they amounted to slightly less than $762 million in the aggregate for the four Central Asian grain importing countries for wheat, wheat flour, and rye flour.

The countries of Central Asia—and perhaps of the broader Caspian region as well—thus have a series of policy decisions to make as they confront these fundamental "rice bowl" issues: how does one ensure food security of a significant portion of the population facing reduced employment opportunities and without access to the means to produce its own food, and how does one ensure delivery of wheat and flour to the rural population? The urban population that depends on ability to purchase food is precisely the stratum of society most likely to foment social unrest if conditions should deteriorate to the point of being intolerable.

The answers lie in the social safety net: feeding programs coupled with income support. Central Asia in the aggregate does not face widespread hunger, but aggregate statistics can hide pockets of despair, and the Central Asian governments would be wise to devote needed funding to assurance of supplies of staple foodstuffs for those unable to produce their own.

AUTHORS

Ambassador (ret.) Allan Mustard, CPC Board Member

Efgan Nifti, Executive Director, Caspian Policy Center Follow @enifti

Ambassador (ret.) Robert Cekuta, CPC Board Member

Ambassador (ret.) Richard Hoagland, CPC Board Member