What The Current Tension Between Washington And Moscow Will Mean For Fighting Corruption In The Caspian Region

Recent Articles

Author: Ambassador (Ret.) Allan Mustard, Ambassador (Ret.) Richard E. Hoagland

03/29/2021

What does the current tension in the U.S.-Russian bilateral relationship portend for these two powers' interactions with Central Asia and the South Caucasus? The U.S. intelligence community's published assessment that Russian actors, on direct orders from President Putin, meddled in the 2020 U.S. election, coupled with President Biden's agreement during an interview that Russian President Vladimir Putin is a "killer," caused the Kremlin to recall its ambassador in Washington, Anatoly Antonov, to Moscow for consultations.

"Recall for consultations" is a turn of phrase meaning relations have been temporarily downgraded to the chargé d'affaires level, a diplomatic snub and warning signal that the recalling capital is significantly upset and makes publicly clear that the bilateral relations are now officially in a seriously difficult stage.

While the Caspian region is not likely in the forefront of either the White House's or the Kremlin's thinking right now, it could well suffer collateral damage or become a skirmish ground for proxy fights as Washington and Moscow square off.

The Kremlin and the White House historically view foreign relations from utterly irreconcilable perspectives. Since World War II, the U.S. approach has been based conceptually on finding shared mutual interests that allow for "win-win" scenarios, despite recent decades' over-militarization of U.S. foreign policy.

The Kremlin, in contrast, views foreign relations as a zero-sum game, in which the other side must lose if Russia is to win. For Russian conservatives, “winning" is an existential issue. From that perspective, political assassination of foes (Litvinenko with polonium, attempts to kill Skripal and Navalny with Novichok), invasions of Georgia and Ukraine, and efforts to manipulate the recent U.S. Presidential election are rational and predictable nefarious acts, particularly if they incur no serious consequences.

This leads to the fundamental question: is the West and, in particular, is America prepared to impose more severe penalties for these violations of international norms? The answer to that question will frame the current situation’s impact on the Caspian region.

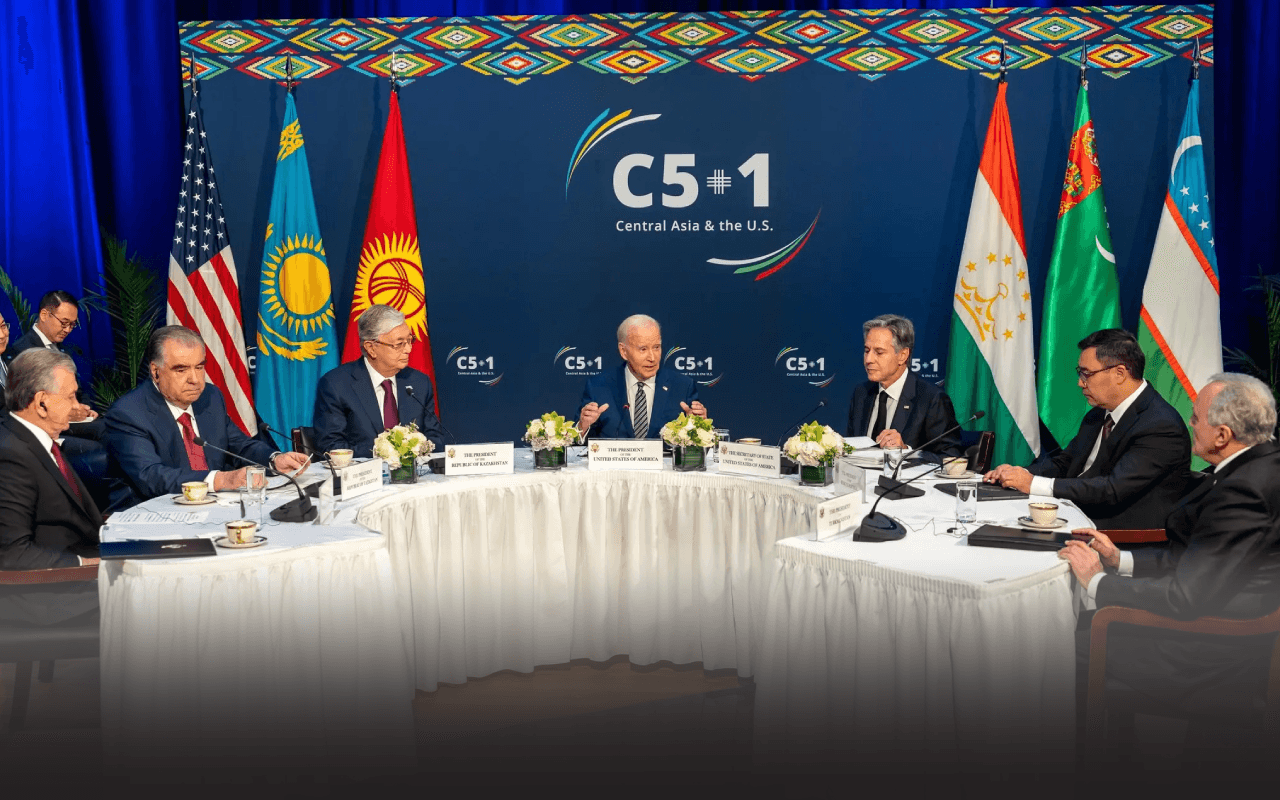

The Biden administration’s vow to fight corruption in foreign countries will certainly affect the eight nations of the Caspian region – Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. All eight are about to celebrate their 30th anniversary of independence. They all, to one degree or another, practice a foreign policy first defined by Kazakhstan as “multi-vector,” meaning that they seek to balance their relations among Russia, China, the European Union, the United States, and, to lesser degrees, Turkey, Iran, and the Gulf Arab states. But the coming weeks and months will test the balance they strive to maintain.

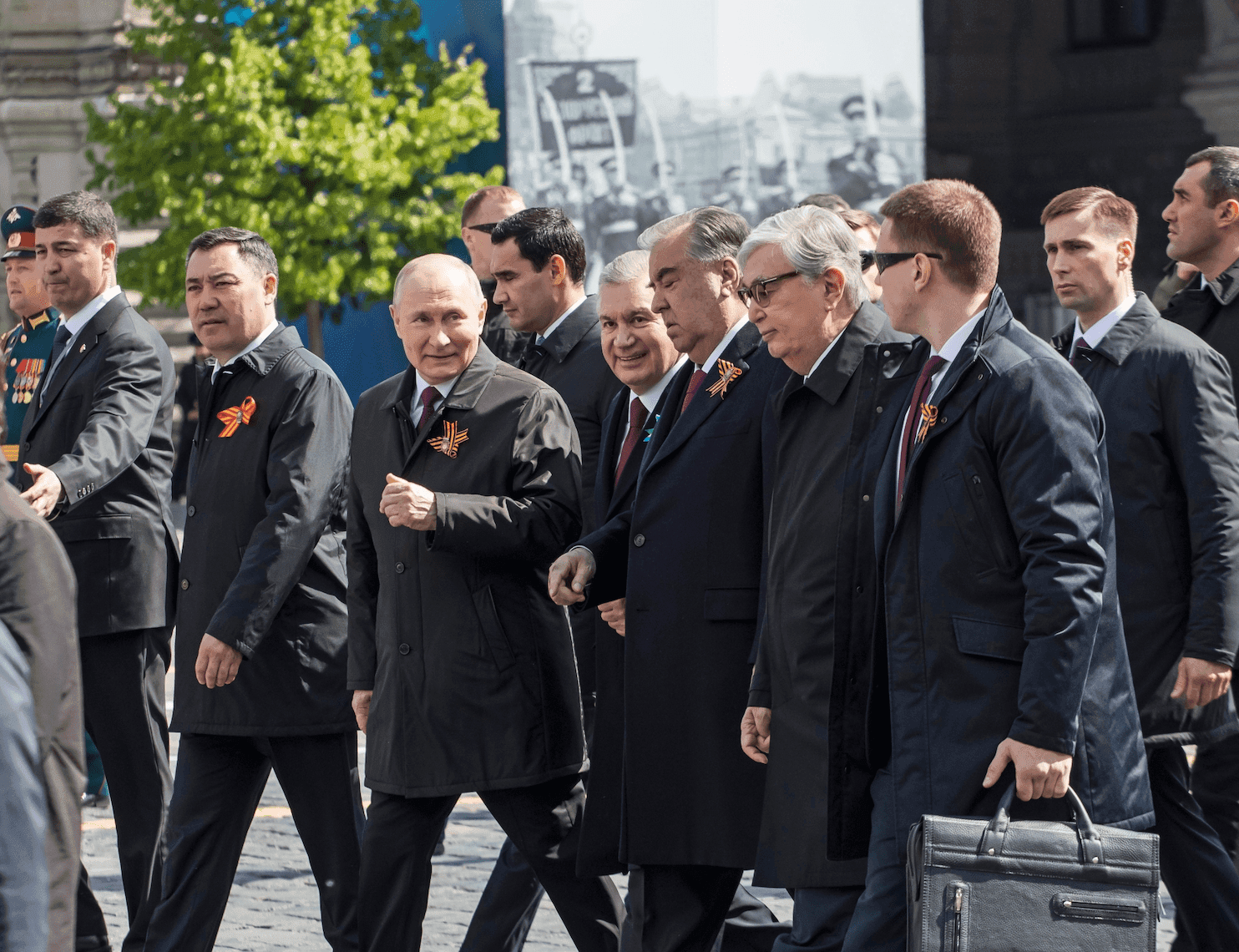

Since his re-election in 2003, Russian President Vladimir Putin has described these countries as part of Russia's "near abroad," falling within Russia’s “special sphere of influence.” Sometimes he goes so far to name them as part of Russia’s “exclusive sphere of influence.” We know from experience that Moscow frequently, if not daily, reminds the leaders of the eight countries against too close of a relationship with the West, and specifically against such a relationship with Washington. Some would argue that Moscow has never worked to resolve the so-called prolonged conflicts (between Armenia and Azerbaijan and in Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine) precisely to keep them from feeling confident enough to choose to gravitate somewhat more toward the West.

None of the eight countries of the Caspian region has a Western heritage that informs how they organize their social and political structures. In almost all of them, the heritage of the various khanates, as well as the Persian, Soviet, and Tsarist empires, remains a strong influence – a state organized around a cult of personality supported by a strong and omnipresent intelligence service that is not at all against collaborating with elements of organized crime whenever that might be useful. This includes making use of mafia dons-turned-oligarchs and quite often significant off-the-books payments that tend to trickle upward into the pockets of the leader and the leader’s family and closest cronies. In plain terms, large-scale corruption is a fully integrated part of governance in most of these countries.

The Biden administration has stated that it will make a global effort to rein in corruption, and this is all well and good. However, if implementation of this policy is done primarily through punitive sanctions and public naming-and-shaming, as all too often happens in the implementation of U.S. foreign policy, in the Caspian region this will merely push the countries closer to Moscow. Already there’s a common perception among these countries that in recent years Washington has lessened its interest in the region. This is not at all true. However, as is often said, perception is reality and needs to be dealt with carefully and creatively.

As former high-level U.S. diplomats ourselves, we know that the most idealistic of policies can coarsen – or at least become somewhat simplistic – as they trickle down through the bureaucracy to those who actually implement them. One reason for this is that working-level diplomats sometimes tend toward easy ideology rather than complex reality, so that they can report back to headquarters, “Message delivered!” This can turn carefully wrought policies into a Cliff Notes version that excises complexities and too often alienates rather than persuades. It goes without saying that working toward success for an anti-corruption policy is a long and difficult process, especially in countries that were once part of the Soviet Union and still have natural affinities, to greater or lesser degrees, with Russia – a state that will never criticize them for corruption.

Further, there is a segment of U.S. foreign policy implementers who like the “feel good” of naming and shaming. Maybe it’s not polite to say so, but it is a reality that colors the day-to-day, on-the-ground practice of our foreign policy. Our senior officials, both in Washington and at our embassies in the region, will need to be vigilant that we do not fall into these traps. Because if we do, we shall surely fail.

To their real credit, U.S. diplomats on the ground are quite frequently expert in the nuances of the countries where they are serving. They know which senior officials might be more open to considering new ideas. After all, true diplomacy is about personal relationships, not press releases and social media posts.

Therefore, to work on lessening corruption in the Caspian Region countries, it will be incumbent on U.S. diplomats to identify discrete areas where there is a real chance that small but noticeable changes can be made. Once that is accomplished in good faith on both sides, then together they can begin to tackle the tougher problems of corruption.

Washington will need to remember that true change is built on mutual trust and takes time. And Washington will also need to remember that Moscow will be fighting this U.S. foreign policy every step of the way.