The Nagorno-Karabakh Peace Deal: Reading Between the Lines

Recent Articles

Author: Austin Clayton

11/16/2020

After more than a month of fighting and dozens of civilian casualties, Armenia and Azerbaijan signed a fourth and final agreement that took effect on November 10. The agreement looks to end nearly three decades of military conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh and the surrounding territories that had been occupied by Armenian forces. Despite the halt to the current fighting, uncertainty still looms as critical details have been left out of the agreement. Further, Russia and Turkey offer conflicting statements about each other’s role in upholding regional stability.

Azerbaijan’s President Ilham Aliyev, Armenia’s Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan, and Russia’s President Putin signed the agreement (mediated by President Putin himself) to put an end to all military hostilities beginning at midnight on November 10.

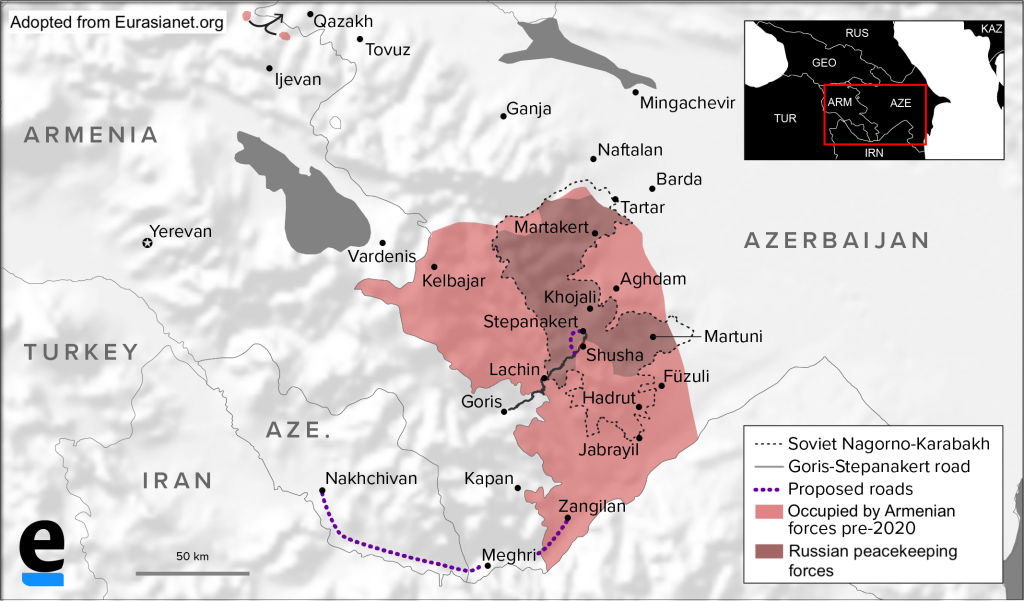

The joint statement released by the leaders of the Russia, Azerbaijan, and Armenia establishes several deadlines for the Armenian de-occupation of Azerbaijani lands. First, Armenia is to return the Kalbajar District to Azerbaijan on November 15 and the Lachin District by December 1. Armenia must also return the territories of Aghdam to Azerbaijan by November 20. Shusha, the city strategically perched above Nagorno-Karabakh’s capital of Khankendi/Stepanakert and captured by Azerbaijani forces on November 8, is to remain in Azerbaijani control.

On the day of the deadline for the Armenian withdrawal from Kalbajar, Azerbaijan announced that it authorized a ten-day extension at the request of Russian President Vladimir Putin, allowing residents until November 25 to vacate Azerbaijani territory. The decision was made based on the complicated terrain of the region, as the road connecting Kalbajar with Armenia cannot accommodate the mass exodus of people. While the extension is beneficial for humanitarian purposes, there is no other change in the return of Lachin and Aghdam provinces as scheduled.

The agreement includes several points regarding connectivity and transport corridors. The Russian Federation will provide a new peacekeeping mission to the Lachin corridor that runs around Shusha and connects Nagorno-Karabakh to Armenia. Russia’s peacekeeping mission will last for five years and will automatically renew for an additional five years if none of the parties issues an objection six months or more in advance. The peacekeeping mission will consist of 1,960 Russian military personnel, 90 armored personnel carriers, and 380 military vehicles and other special equipment. The settlement also includes a clause for establishing a transport corridor between Azerbaijan and its exclave, the Nakchivan Autonomous Republic. This link will allow citizens and cargo to transit Armenian territory, and its security will be guaranteed by Russian Border Service authorities. This provision seems to re-establish the land transport between Baku and Nakchivan that existed in Soviet days and was cut in the first Karabakh War in the early nineties.

Before the original Karabakh war, Nakchivan was connected to the rest of Azerbaijan through a railway system. After that war and the closing of borders between Armenia and Azerbaijan, Nakchivan was connected to the outside world through roadways connecting the exclave with Turkey and Iran, and with heavily subsidized flights through Iranian airspace to Baku. There was also a route through Iran to Nakchivan for Azerbaijani truckers. With the new agreement construction of new transport infrastructure to the exclave is envisioned.

Despite specific stipulations and a concrete timeline covering certain matters, the agreement has been criticized for not addressing several critical elements. Notably missing from the pact is a decision on Nagorno-Karabakh itself. The agreement does not define and establish the current or expected status of Nagorno-Karabakh; and in the short term, ethnic Armenians retain control of territory that had not been reclaimed by the Azerbaijani military. This ambiguity might well provide for the establishment of Nagorno-Karabakh’s autonomous status within Azerbaijan, which was one of the contributing factors of the Karabakh conflict in the 1990s.

Another part of the puzzle involves Turkey. Turkey has long backed Azerbaijan politically as well as though sales of military equipment. Although Turkey did not have a direct role in the conflict, it provided some counterbalance to Moscow. At the same time, Armenia and others have charged Ankara with encouraging the war even though Russia continued supplying weapons on credit to Armenia after fighting broke out in July 2020 on the international border between Armenia and Azerbaijan. (Russia also sold weapons to Azerbaijan over the years).

Despite Turkey’s involvement and numerous conversations between Russian and Turkish officials, Turkey’s specific role is conspicuously absent in the joint statement. Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev stated that Turkish military forces will be part of the peacekeeping mission, and a Russian news report indicates that Russia and Turkey will jointly manage a “ceasefire monitoring center” in Nagorno-Karabakh. Dmitry Peskov, the spokesman of the Russian President, has stated Turkey’s involvement is limited to the monitoring center, and Turkish forces will not be part of the peacekeeping mission. On November 11, however, President Erdogan said that Turkish forces will be part of the peacekeeping mission to monitor the deal reached with Russia.

While Azerbaijanis took to the streets and celebrated the opportunity to return to their homes, ambiguities in the peace deal could cause future disagreements. The text reads that “internally displaced persons and refugees return to the territories of Nagorno-Karabakh and adjacent areas under the control of the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Refugees.” Armenians, nevertheless, are fleeing homes out of fear of Azerbaijan, burning them as they leave. Moreover, a report by International Crisis Group indicates the potential for competing property claims between Azerbaijanis returning to the territories and ethnic Armenians remaining or returning to the region.

Ambassador Richard Hoagland, a Caspian Policy Center Advisory Board member, stated that returning home will not be an easy process, even with help from the UN High Commission for Refugees. He noted that over the decades, Armenia has destroyed thousands of Azerbaijani homes and villages, leaving nothing but rubble. A new humanitarian crisis is likely to develop as thousands of internally displaced Azerbaijanis return to their traditional homes. Further, at least some of the Armenians Yerevan settled over the decades in Azerbaijani territory will now flee to Armenia and require international assistance.

Washington hosted the Foreign Ministers of Armenia and Azerbaijan for separate talks during October in Washington, D.C. and had further conversations with the two countries’ leaders, but seems to have played much less of a role than many expected. Russia may be largely responsible for stopping the fighting, but there is considerable room and need for the United States to play an active role in peace building and breaking the cycle of conflict.

The United States has great experience and expertise in helping build peace in post-conflict situations, noted Ambassador Robert Cekuta of Caspian Policy Center’s Advisory Board. Building, not just keeping peace between Armenia and Azerbaijan should be the priority of the United States, and the United States should actively engage Armenians and Azerbaijanis to do so. Americans, he added, have the knowledge and resources to help Azerbaijanis find ways to rebuild understanding, to live together in peace, and to build a future that benefits both sides. While this might sound idealistic at the moment, Ambassador Cekuta points out recent history provides many examples of enemies becoming allies. Even some of the United States’ closest allies were at one time its bitter foes.