Mapping Central Asian Enclaves

Recent Articles

Author: Dante Schulz

12/03/2021

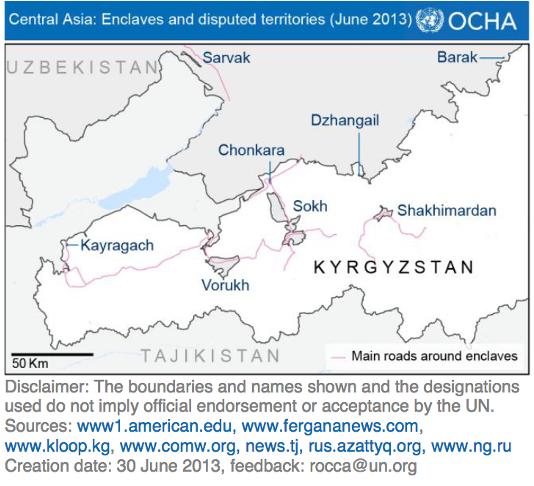

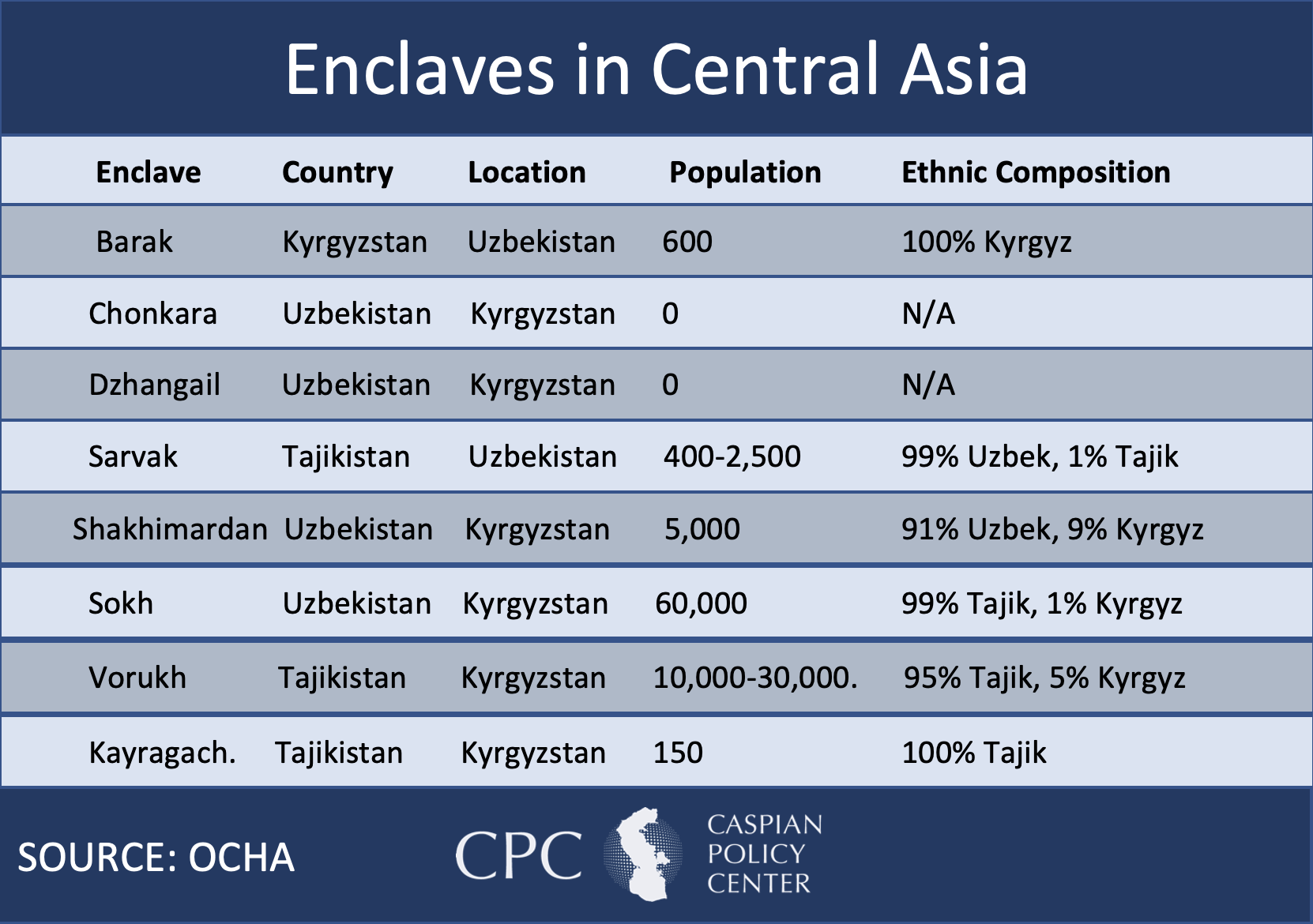

Eight large enclaves dot the Central Asian landscape, isolating about 100,000 residents in the Ferghana Valley from their central governments. Although three of these enclaves boast fewer than 10,000 residents and two are solely used for pastures, the three largest enclaves – Sokh (Uzbekistan within Kyrgyzstan), Vorukh (Tajikistan within Kyrgyzstan), and Shakhimardan (Uzbekistan within Kyrgyzstan) – could pose critical security issues for the Central Asian republics if border incidents continue to persist. Enclaves spanning the Ferghana Valley have proven unsustainable when countries implement stringent border regulations in response to border disputes and disagreements over demarcation arrangements. In addition, the enclaves are hotspots for conflict. Between 1989 and 2009, the Ferghana Valley experienced about 20 armed conflicts. Furthermore, Kyrgyzstan registered 37 border incidents in the valley in 2014 alone. Warming relations among the Central Asian republics would likely mitigate border tensions, but more concerted efforts are needed to remedy the complex Ferghana Valley border situation.

Several enclaves have gained infamy as sources of sustained border tension. The Vorukh enclave, home to about 30,000 people of primarily Tajik ethnicity, is completely engulfed by Kyrgyzstan. Disputes over the border demarcation between Bishkek and Dushanbe for the Vorukh enclave have erupted in a handful of armed conflicts and tense standoffs. In January 2014, five Kyrgyz and two Tajik border guards were hospitalized following a shootout between the Tajik village of Vorukh and the neighboring Kyrgyz village of Ak-Sai. In the previous year, several Tajik residents had clashed with Kyrgyz road workers over controversies stemming from the Kyrgyz construction of a road on land contested by both countries. Fighting resumed once again in July 2019, prompting officials to institute a three-day road blockage after two people were killed and 30 were injured in the fighting.

The presence of enclaves also serves as an impediment to economic growth in the Ferghana Valley. Often, transiting between an enclave and the respective country’s mainland requires a traveler to cross four border checkpoints and numerous police stations. For example, the Shakhimardan enclave relies on its picturesque landscape to fuel its tourism industry. However, tiresome border crossings discourage visitors, thus endangering the livelihoods of the enclave’s residents. In addition, COVID-19 border closures and restrictive regulations on international travel have hampered the enclave’s economic model.

Officials have long blamed remnants of the Soviet legacy in Central Asia for the Ferghana Valley’s present-day border complexities. Under the Soviet Union, the heavily populated Ferghana Valley was divided up into administrative districts with little resemblance to its ethnic composition or regard for its geographical terrain. This strategy enabled Moscow to rule over an expansive region without fear that a unified Central Asian state in the Ferghana Valley could mobilize against its authority. Following the collapse of the USSR, the Central Asian republics adhered to the border demarcations from the Soviet Union. However, this method of border demarcations alone has proven impractical. Different governments rely on maps from different time periods. For example, the Vorukh enclave switched from the Tajik SSR to the Kyrgyz SSR within a seven-year period in the 1940s. While Soviet border demarcation strategies conceived this issue, the Central Asian republics have been reluctant to adapt to the changing geopolitical landscape by tackling these urgent concerns.

Nevertheless, Central Asian governments have prioritized resolving border disputes to alleviate burdens placed on enclave residents. On April 1, 2021, Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan inked an agreement that reopened the road connecting the Sokh enclave and the Uzbekistan mainland. This road allows residents of the enclave to travel to the mainland daily to trade with their compatriots and attract more business. Moreover, Tashkent has promised to construct an airport in Sokh and attract investment opportunities to the enclave. The inaugural re-opening of road traffic between the Sokh enclave and the Uzbekistan mainland is evidence of the region’s desire to resolve its past disputes and could hint at more optimistic prospects for the Ferghana Valley. Governments must adopt actionable policies to resolve the enclave complexity in the Ferghana Valley and ensure economic development for all of its residents.