DAS George Kent’s Remarks at the Caspian Policy Center’s Webinar: A New Caspian Policy for the New Administration, March 3, 2021

Recent Articles

Author: Caspian Policy Center

03/04/2021

Good morning, everyone. It is great to be back with the Caspian Policy Center and with all of you today. I’d like to thank Ambassador Hoagland, with whom I served in Tashkent, Uzbekistan, at the start of my foreign service career in the early 1990s, Ambassador Cekuta, Drs. Kangas and Todd, and Efgan Nifti and colleagues at the Caspian Policy Center for putting together this virtual event.

We are now six weeks into the Biden Administration. As Professor Kangas noted, the ranks of policy makers nominated and confirmed continue to fill out; even so, we are conducting policy reviews and developing new approaches to existing challenges.

But it is important to underscore that the United States’ strategic interest support for a democratic, prosperous, peaceful, and secure South Caucasus and Greater Caspian region remains steadfast.

To frame today’s session, I’d like to share my perspective on some of the security, governance, and development challenges – and also opportunities for deeper partnership – in this region. Please keep in mind, as I’ve noted in past CPC sessions on the margins of the UN General Assembly in New York, that the State Department’s regional bureaus divide the Caspian basin between Central and South Asia and the Caucasus/Europe, my area of responsibility.

Regional Security

Let’s start with regional security, given the dramatic developments in 2020. When I first began meeting with Foreign Ministers and other officials from the Caucasus in 2018, they would usually frame their countries’ century-long challenge as existing within a triangle of traditional empires and modern successor states – Russian, Persian/Iranian, and Ottoman/Turkish. Central Asian states would add China to that mix.

In 2020, what has been called the Second Karabakh War acted as a geostrategic earthquake. After 44 days of intense fighting and a subsequent Russian-imposed ceasefire arrangement, Azerbaijan, with Turkish support, reestablished control over parts of Nagorno-Karabakh and its seven formerly occupied territories for the first time since 1994.

The Russia-brokered November 9 ceasefire arrangement left many key issues underlying the conflict unresolved, including the final status of Nagorno-Karabakh. Secretary Blinken has committed to reinvigorating U.S. engagement on Nagorno-Karabakh and bolstering support for the OSCE Minsk Group process, which the United States co-chairs along with France and Russia, designed to facilitate Armenia and Azerbaijan charting a path forward.

In addition to a strengthened and more confident Azerbaijan, another result of the conflict and ceasefire arrangement is that external powers are newly assertive in the region.

With the introduction of nearly 2,000 Russian “peacekeepers,” there are now Russian boots on the ground in all three South Caucasus countries for the first time since the breakup of the Soviet Union in 1991. After the battlefield loss by ethnic Armenian forces, Armenians feel even more reliant on Russia as a guarantor of security. Meanwhile, Russia still refuses to withdraw its troops from Georgia, despite obligations it undertook as part of a 2008 ceasefire.

Turkey, too, has returned to the region with a military presence for the first time in a century, since 1920. On the trade front/flip side, there may be new opportunities to realize the delayed promise of the 2009 agreement between Turkey and Armenia.

Iran also is posturing to play a larger role in the South Caucasus, following the fall 2020 fighting in the region. Tehran has stepped up diplomatic engagement with all three South Caucasus countries but was largely on the sidelines during the recent fighting. Without a formal role in the ceasefire arrangement, Iran may, in some respects, be finding itself on the outside looking in.

Meanwhile, in Central Asia, China’s One Belt One Road initiative promises infrastructure but often brings debt and limited benefits to the local population. The goal of China’s state-owned enterprises and banks appears to be to create political leverage for the Chinese government and extract the benefits of that investment for China.

Central Asia can be linked to the world, not just to China, through international private sector investment if governments in the region institute and commit to reforms to improve the business climate.

Good Governance and Judicial Independence

That is where good governance and judicial independence play a crucial role. For its part, the United States is committed to working with the countries of the South Caucasus and Greater Caspian region to create the conditions needed to unlock greater private investment, combat corruption, and secure nations’ autonomy from foreign malign influence. We will continue to promote transparency, openness, rule of law, and respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms.

It is worth emphasizing that a justice system with integrity benefits both a country’s citizens and foreign investors creating jobs, driving prosperity and growth.

Some countries in the region have made positive steps forward. The Presidents of Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan have initiated reform programs to strengthen democratic governance and expand space for civil society.

In Armenia, the United States has expanded assistance to Armenia following the 2018 Velvet Revolution. Prime Minister Pashinyan’s government has admirably remained committed to a reform agenda that will benefit Armenian society, despite the upheaval following the recent ceasefire.

Of course, many challenges remain. In Azerbaijan and in Central Asia, we continue to press for enhanced respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms and the rule of law, including the release of individuals widely considered political prisoners and detainees.

Meanwhile, the recent political developments in Georgia illustrate the need for Georgia to reinforce its commitment to democratic principles, strengthen judicial independence, and level the electoral playing field if it is to realize its European and EuroAtlantic aspirations.

Economic Opportunities

As we offer support to countries in the region on democratic development, the United States also continues to see great potential for regional economic cooperation among the Caspian nations and their neighbors.

Overshadowed by the ongoing pandemic and the outbreak of the fall conflict, the Southern Gas Corridor was completed under budget and on time, with the final Trans Adriatic Pipeline segment to Italy completed in December 2021. The United States’ and the EU’s sustained support for this multinational public-private partnership was part of our long-term goal to improve European energy security and diversify gas supplies to Europe.

In January, Azerbaijan signed an MOU with Turkmenistan on joint exploration of hydrocarbons in the Caspian. This breakthrough, after years of impasse, has the potential to lead to greater connectivity between the existing energy infrastructure spanning the South Caucasus and the significant hydrocarbon resources of the Greater Caspian Basin.

This initiative could be a game-changer – with rational, economic self-interest overcoming long-standing hurdles to an interdependent regional network. Talks of cross-Caspian trade, previously hostage to the disagreement between the Caspian littoral states, have begun in earnest. The most recent announcement was plans to expand Kazakhstan’s Port Aktau to enable the export of goods to Azerbaijan, and onwards to Turkey and Europe.

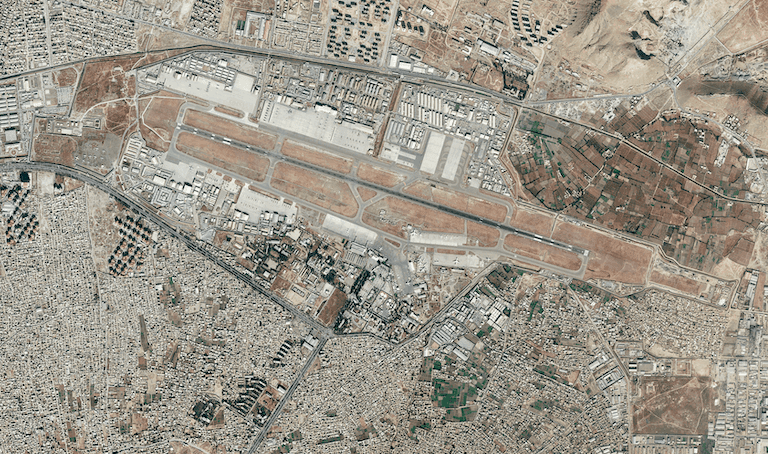

Meanwhile, Afghanistan sees the Caspian region as a key potential export route for its goods via the Lapis Lazuli corridor. This multi-modal corridor has the potential to allow Afghanistan access to Turkish and European markets via Turkmenistan, Azerbaijan, and Georgia.

Enhancing regional connectivity and promoting economic opportunity for all are among the essential ingredients in this vision. The same applies across the Caspian in the South Caucasus.

The United States shares the region’s goal of developing modern infrastructure, diversifying sources of energy, and building competitive market environments. The United States is committed to promoting connectivity that advances national sovereignty, regional integration, and trust. And American companies are ideally suited to build modern, secure, and reliable infrastructure, and to implement advanced information and communications technology systems in the region.

In conclusion, I’m optimistic that the increasing connectivity and economic integration of Caspian and South Caucasus countries – with the support of the United States and our partners – has the potential to bring lasting stability and prosperity to the region.

Watch the full remarks