In Much of Central Asia, Perception of China Declines

Recent Articles

Author: Nicholas Castillo

08/19/2024

Tajikistan’s Chinese-run Zarafshon gold mine is reportedly wreaking havoc on the local environment and public health. Neighboring communities appear to be aware of this, having sent a letter in 2022 to Tajik authorities noting, "[Villagers] are getting sick more often...the number of stillborn babies has increased." This is one of the more extreme examples of the negative impacts from Chinese-run projects in Central Asia that are increasingly calling into question the impact of the investments China has poured into the region in the past decade. This fact seems to be affecting China’s public image, which opinion polling shows is on decline in much of Central Asia. Throughout the region there is evidence that locals do not believe they are reaping sufficient benefits from Chinese investments. Now, anti-Chinese sentiment seems to be on the upswing as Central Asians take notice of unwelcome changes brought by Chinese companies and state-run entities.

One of the likely drivers of dissatisfaction surrounding Chinese investment in Central Asia relates to who exactly staffs projects run by Chinese firms. In opinion polling, Kazakhs and Uzbeks strongly oppose the common Chinese practice of bringing in foreign Chinese workers to staff massive infrastructure and investment projects, a practice Beijing has continued. Tensions over the issue have boiled over into protests and even mob violence throughout Central Asia.

In terms of inter-personal dynamics, unlike Russians or Turks, Chinese transplants have a completely different cultural profile from locals. Mandarin fluency is low in Central Asia in contrast to Russian, or even English. There is evidence of positive encounters between Chinese workers and locals, but bad impressions seem more impactful, especially relating to workers brought for infrastructure projects. When reached for comment, long-time Central Asia journalist and researcher, Bruce Pannier, explained that while there can be hostility between Russians and Central Asians, there is also sense of familiarity. Chinese arrivals are much newer group and rarely intermix with the locals. Speaking of the lack of interactions between Chinese workers and Central Asians, Pannier relayed, “I asked Kyrgyz about [Chinese workers] and they said, we never mix with them at all.... [Chinese workers] have a camp, it’s got a chain link fence around it.... At the end of the day all those machines go inside this chain link fence with these trailer structures, which is where all the [Chinese] workers live, and they lock the gate.”

Moreover, the quality and impact of Chinese investments might be coming under increased scrutiny. A 2021 study found that 35% of projects run by China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), Beijing's flagship investment program, have involved controversies around corruption, excessive debt, and labor exploitation. The long-promised Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan-China rail line faced numerous delays before moving forward with construction. Similarly, the China-Central Asia Line D gas pipeline has been mired down in delays since 2019. High profile incidents, like the repeated failure of the Chinese-refurbished Bishkek Thermal Power Plant and public health and corruption issues surrounding the Chinese-run Kara-Balta Oil refinery, seem to have also contributed to a decline in prestige for Chinese projects. In Kyrgyzstan, only 19% of people report strongly supporting Chinese investment in energy and infrastructure projects, while 31% strongly opposing such projects. “If you’re living in Bishkek,” remarked Pannier, “and someone says [infrastructure] is built in China or the Chinese are coming to fix this, you’re already going to go, ‘Yeah, well, sure.’ In the meantime, that hasn’t worked out too well.”

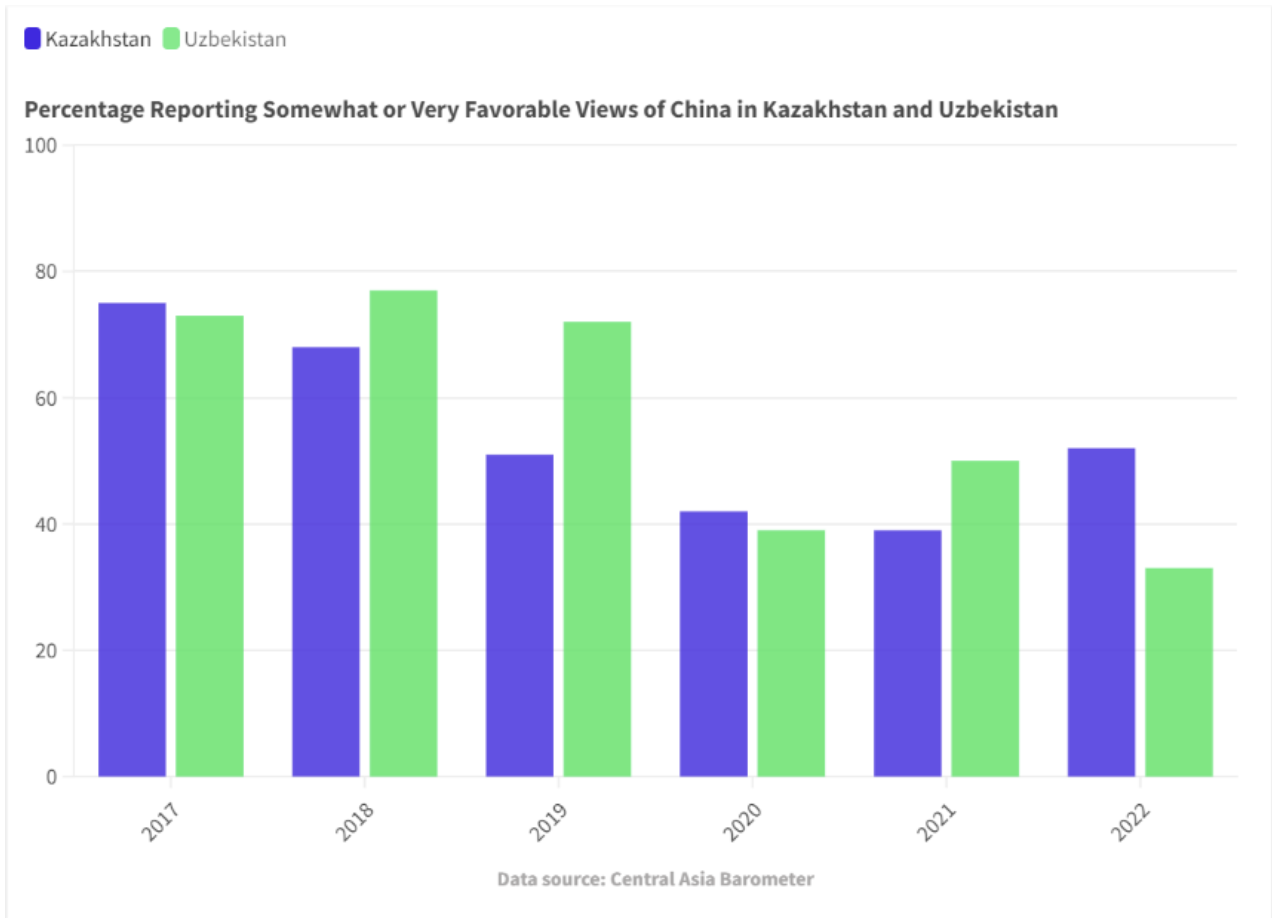

The declining prestige of Chinese projects has coincided with, and is likely contributing to, a broad downtick in opinion toward China in much of Central Asia. Opinion polling demonstrates a notable decrease in positive attitudes, especially in the two most populous Central Asian states, Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. In Kazakhstan, the portion of the population that viewed China as somewhat or very favorable shrank from 75% in 2017, to a low of 39% in 2021, before bouncing up to 51% in late 2022. Uzbekistan’s shift has been more dramatic, going from 73% favorability in 2017 down to 32% by 2022.

Kyrgyzstan appears to have had a more consistent and more positive attitude toward China and has not seen the steep declines of Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan. In dire need of the investment and infrastructure offered by Chinese firms, Kyrgyz respondents tend to have a consistent favorability rating for China usually within 5 points of 50% in any given year or poll.

Kyrgyzstan appears to have had a more consistent and more positive attitude toward China and has not seen the steep declines of Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan. In dire need of the investment and infrastructure offered by Chinese firms, Kyrgyz respondents tend to have a consistent favorability rating for China usually within 5 points of 50% in any given year or poll.

Tajikistan appears to have static net-positive views of China and Beijing’s relations with the region. World Gallup polling shows a consistent favorability rating for China in Tajikistan, between 60% and 70% of respondents throughout the 2010s. Central Asia Barometer reported in late 2022 that 60% of Tajik respondents felt China is either somewhat friendly or very friendly toward Tajikistan.

This would appear to be paradoxical at a first view, given the uniquely high toll Tajikistan has paid for relations with Beijing. Tajikistan is the only Central Asian state to have lost territory to China, ceding 1000 square kilometers to China in 2011. Anecdotal evidence points to localized anger at Chinese projects. But the answer pointed to by various analysts as to why mass attitudes have not shifted in Tajikistan is the country's highly controlled political and media environment, where discussions of China’s negative impact can be stifled to a greater degree than in other states.

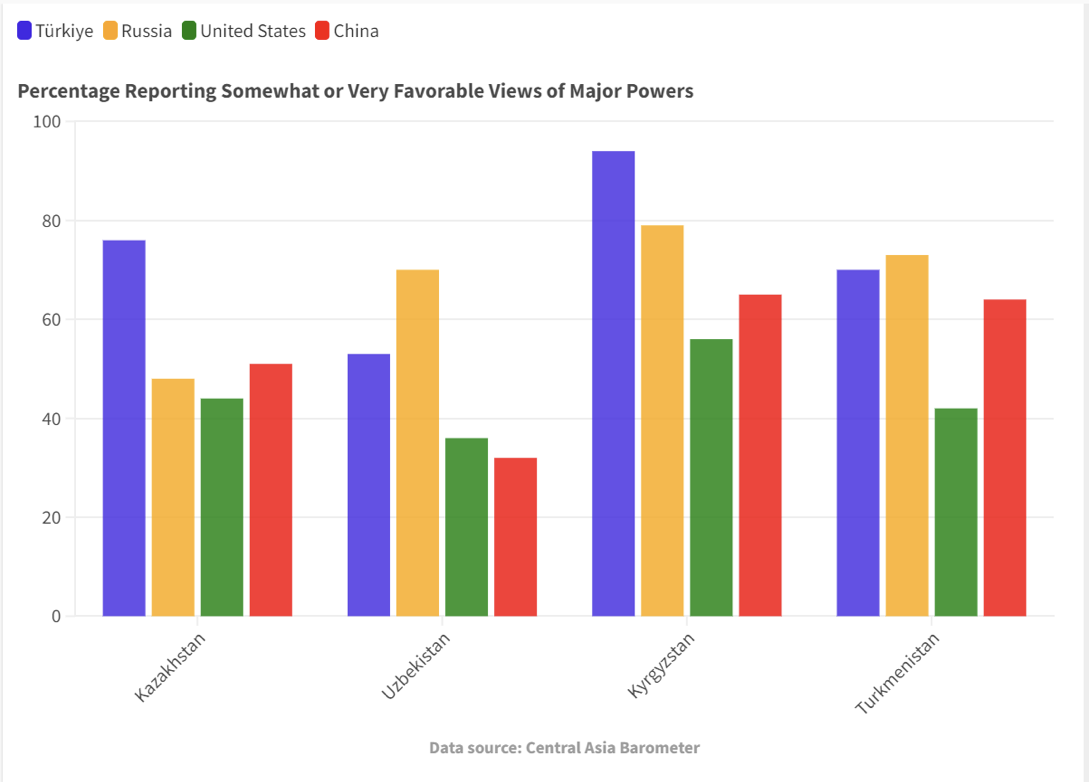

Nevertheless, across Central Asia when compared with other major global actors, opinion of China lags. Even after Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine, Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan have significantly more positive views of Russia than of China, especially in the case of Uzbekistan where the favorability gap was 40%. Kazakhstan, regularly in the crosshairs of Russian nationalists given its long, shared border and ethnic Russian minority, appears to be an outlier with more significant anti-Russian attitudes after February 2022. Opinion of China does however often outperform opinion of the United States, although only by a few points. These trends are consistent across countries polled, including even in isolated Turkmenistan, although accurate data on this question does not appear to be available yet for Tajikistan.

There are some country-specific issues that could be causing a downward trend in views of China. In Kazakhstan, the mass persecution of Uighurs in China has long produced notable public demonstrations. Kazakhs are more likely to have relatives from Xinjiang or encounter Uighur and Kazakh refugees from the region. Studies show that the spread of Covid-19 negatively impacted views of China in Central Asia, hinting at why 2020 seems to be a major drop-off point in some countries, especially Uzbekistan.

But across Central Asia, the Chinese public investment that came with high promises is now generating apathy or even hostility . The example of the Zarafshan mine demonstrates that Central Asians are not ignorant of the negative impact of Chinese-run projects, even if they are not fully able to voice their anger. Central Asians are also cognizant of the fact that Chinese investment does not come without strings attached, with Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan suffering from large and often untenable debts to China. Polling from even comparably China-friendly Kyrgyzstan indicates that 66% of respondents report being very concerned about debt relating to Chinese projects, while another 21% are somewhat concerned.

China has worked to adapt to this increasingly hostile environment. At the insistence of Central Asians governments, Chinese firms have worked to make more local hires, adapted to local conditions, and work in better concert with local authorities. China’s approach is also increasing its emphasis on green energy projects in the coal-reliant region. But results of these new efforts have been mixed and done little to stem the tide of rising anti-China sentiment in the region.

This is not to say that the benefits of Chinese engagement in the region should be entirely discounted. China’s involvement in Central Asia is likely a net-benefit, bringing needed goods and infrastructure to a long impoverished and isolated region still recovering from a century of Soviet domination. But perceptions can be just as crucial as objective realties, and if Beijing and Chinese firms don’t fully address concerns around employment opportunities, debt, corruption, reliability, and environmental impacts then anti-Chinese sentiment might well continue to grow in the region.

China announced the BRI in Astana, Kazakhstan, in 2013, but with newer Western initiatives like the European Union’s Global Gateway or G7’s Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment now acting as alternatives to Chinese projects, Beijing might lose out in the long term, if other programs can take advantage of China’s declining reputation. Chinese investment is already becoming less attractive throughout the region and Chinese foreign direct investment is actually on the decline from its heights in the mid-2010s.

Public opinion of China appears to be on the decline in Central Asia. Beijing might try to tackle issues surrounding employment and local impacts. But while China is making some shifts, there does not seem to be a major change in course around employment quality or environmental responsibility. Western governments can capitalize on this, now that they are equipped with multilateral mechanisms for investment. The inattention of Chinese firms might be to their own detrirment as public opinion continues to turn against Beijing.